(when all of your central vision is almost gone and the rest will be gone within 5 years because of an incurable eye disease, cone dystrophy)

Not really to not see, but to see differently, strangely, queerly, sideways and slantways and in ways that aren’t seen as seeing

2 goals for my work on vision, version 1

First, a critical intervention in the privileging of vision/sight—an exploration of other ways of attending and other language for that attention. Not just seeing but listening and feeling. What might be some aural-centric words to counter vision, insight, focus? In tune, in harmony, I hear what you’re saying?

Thinking about this reminded me of a poem I memorized this summer: And Swept All Visible Signs Swept Away/ Carl Phillips

Easy enough, to say it’s dark now.

But what is the willow doing in the darkness?

I say it wants less for company than for compassion,which can come from afar and faceless. What’s a face, to a willow?

If a willow had a face, it would be a song. I think.

I am stirred, I’m stir-able, I’m a wind-stirred thing.

Here, I’m thinking about listening and the expression of self through song, as opposed to through face and vision. The “visible signs” have been swept away by the wind, yet compassion and recognition (to beholden) are still possible.

Second, an expansion of what vision/seeing is—how do we see, what does it mean to see? what are others ways of seeing are possible? what are the different ways I do/can use my vision (e.g. peripheral instead of central)? This second project is inspired by Georgina Kleege’s book Sight Unseen and the descriptions of her own ways of seeing–even though she is legally blind, she likes to go to movies and art museums. She can still watch the movies and see the paintings, just in different ways.

At the end of her introduction to Sight Unseen she writes

…my goal is not merely to expose my blindness to the reader’s scrutiny; some general insight can come from introspection. I also hope to turn the reader’ s gaze outward, to say not only “Here’s what I see” but also “Here’s what you see,” to show both what’s unique and what’s universal. I invite the reader to cast a blind eye on both vision and blindness, and to catch a glimpse of sight unseen (5).

Sight Unseen/ Georgina Kleege

2 goals for my work on vision, version 2

First, to grow accustomed to the dark and to study how life steps almost straight:

We grow accustomed to the Dark –/ Emily Dickinson

We grow accustomed to the Dark –

When light is put away –

As when the Neighbor holds the Lamp

To witness her Goodbye –

A Moment – We uncertain step

For newness of the night –

Then – fit our Vision to the Dark –

And meet the Road – erect –

And so of larger – Darkness –

Those Evenings of the Brain –

When not a Moon disclose a sign –

Or Star – come out – within –

The Bravest – grope a little –

And sometimes hit a Tree

Directly in the Forehead –

But as they learn to see –

Either the Darkness alters –

Or something in the sight

Adjusts itself to Midnight –

And Life steps almost straight.

Second, to stay and delight in the mystery and magic that the dark can provide:

A Murmur in the Trees – to note – / Emily Dickinson

A Murmur in the Trees – to note –

Not loud enough – for Wind –

A Star – not far enough to seek –

Nor near enough – to find –

A long – long Yellow – on the Lawn –

A Hubbub – as of feet –

Not audible – as Ours – to Us –

But dapperer – More Sweet –

A Hurrying Home of little Men

To Houses unperceived –

All this – and more – if I should tell –

Would never be believed –

Of Robins in the Trundle bed

How many I espy

Whose Nightgowns could not hide the Wings –

Although I heard them try –

But then I promised ne’er to tell –

How could I break My Word?

So go your Way – and I’ll go Mine –

No fear you’ll miss the Road.

from my chapbook, How to Be When You Cannot See

A poem about how to B when you cannot C/ Sara Lynne Puotinen

Anxious adjustments

Barely visible buoys blinding bright big beach little beach bridge spanning

Cedar avenue congested cars clear lake cloudy vision

Dodging ducks and drifting swimmers dark triangular shapes disappearing

Emptied mind, emptied lake, everything erased by eroding eyes

Fogging

Goggles getting off course gaining perspective on not seeing only feeling

How to swim straight how to be when you cannot see

Isolated isosceles

Jumbled views

Kayaks keeping out menacing boats

Lifeguards lining the course

Muscles moving then stopping to sight

mid-lake motionless

messed up maculas magically making bright orange buoys disappear reappear then disappear again

Nothing to sight but

Opaque water occasionally the color of

Pea soup thick hiding Northern Pike Yellow Perch a percolating panic is

Quelled even as quirky gaps in my central vision

Remain removing random objects, often red ones I

Swim without seeing showing off strong shoulders and straight strokes.

Touching toes testing limits tracking towering light poles tired yet triumphant

Unbroken

Victorious

Weightless worry-less wiser

eXiting the water with a silent joyful exuberant

“Yes!” to an audience of yellow paddle boats yelling kids and my yellow backpack its many

Zippers zipped, indifferent to my effort unfazed by my exhaustion

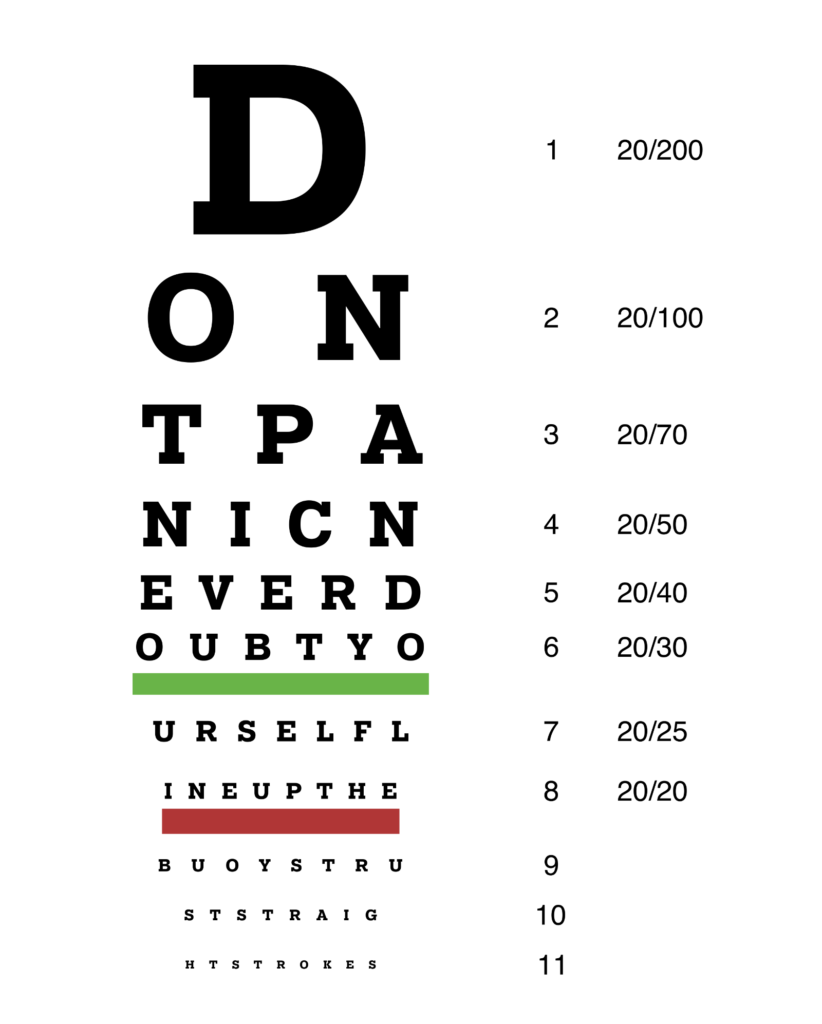

One of my Snellen chart poems:

How to Be When You Cannot See, Some Strategies

- Learn to listen

- Learn how to pay attention, then memorize the path

- Accept, accommodate, adapt

- Ask for help

- Read, write, search for better words

from reflections on my mood ring poem, Resilient

Tips and Tricks

- When you’re in the checkout line at Target with your husband, make sure to notice the lane number if you have to leave the line, because when you return you won’t recognize him, but you’ll recognize the number.

- Figure out how many seconds it takes to fill up your water bottle (or glass or mug) then count to that number as you refill it–even when you can’t see the water you won’t spill because when you reach the magic number you’ll know it’s filled.

- If you have identical containers for your sugar and flour, write in giant letters across each, “FLOUR” and “SUGAR” so you don’t accidentally put sugar in the flour, or flour in the sugar.

- When it gets too hard to see letters, read with your ears instead of your eyes; listen to audio books.

- To see someone’s face, look at their shoulder.

- Triple check that you have the right toothbrush (and not your daughter’s) before brushing your teeth. Consider moving yours or putting a rubber band around the bottom.

Ask for Help

- Always ask someone else to check if there is mold on the food before using/eating it, especially cheese and bread.

- Ask someone to explain what’s happening on a television show, especially one with lots of fast action, but only when you think it’s important. Otherwise, just learn to live with not knowing what’s happening.

- When someone wants to show you a meme or a picture, ask them to explain what you are looking at so you don’t panic when you can’t see it, or hurt your brain trying to figure it out.

- If possible, always go with someone else to a public bathroom in a new place. They can tell you which one is for women, which for men. In a better world, ALL bathrooms would be gender neutral so this wouldn’t be a problem–for you, or, more importantly, for a lot of other people who urgently need them

Robin Wall Kimmerer and Learning to See

A Cheyenne elder of my acquaintance once told me that the best way to find something is not to go looking for it. This is a hard concept for a scientist. But he said to watch out of the corner of your eye, open to possibility, and what you seek will be revealed. The revelation of suddenly seeing what I was blind to only moments before is a sublime experience for me. I can revisit those moments and still feel the surge of expansion. The boundaries between my world and the world of another being get pushed back with sudden clarity an experience both humbling and joyful.

Gathering Moss/ Robin Wall Kimmerer

Annie Dillard and “Seeing”

But there is another kind of seeing that involves a letting go. When I see this way I sway transfixed and emptied. The difference between the two ways of seeing is the difference between walking with and without a camera. When I walk with a camera I walk from shot to shot, reading the light on a calibrated meter. When I walk without a camera, my own shutter opens, and the moment’s light prints on my own silver gut. When I see this second way I am above all an unscrupulous observer.

It was sunny one evening last summer at Tinker Creek; the sun was low in the sky, upstream. I was sitting on the sycamore log bridge with the sunset at my back, watching the shiners the size of minnows who were feeding over the muddy sand in skittery schools. Again and again, one fish, then another, turned for a split second across the current and flash! The sun shot out from its silver side. I couldn’t watch for it. It was always just happening somewhere else, and it drew my vision just as it disappeared: flash, like a sudden dazzle of the thinnest blade, a sparking over a dun and olive ground at chance intervals from every direction. Then I noticed white specks, some sort of pale petals, small, floating from under my feet on the creek’s surface, very slow and steady. So I blurred my eyes and gazed towards the brim of my hat and saw a new world. I saw the pale white circles roll up, roll up, like the world’s tuning, mute and perfect, and I saw the linear flashes, gleaming silver, like stars being born at random down a rolling scroll of time. Something broke and something opened. I filled up like a new wineskin. I breathed an air like light; I saw a light like water. I was the lip of a fountain the creek filled forever; I was ether, the leaf in the zephyr; I was flesh-flake, feather, bone.

When I see this way I see truly. As Thoreau says, I return to my senses.

“Seeing”/ Annie Dillard

Dillard doesn’t mention peripheral vision in this passage, but that is what she’s describing.

Some of my Vision Resources.

Edgar Allen Poe and Peripheral Vision

To look at a star by glances—to view it in a side-long way, by turning toward it the exterior portions of the retina (more susceptible of feeble impressions of light than the interior), is to behold the star distinctly—is to have the best appreciation of its lustre—a lustre which grows dim just in proportion as we turn our vision fully upon it. A greater number of rays actually fall upon the eye in the latter case, but, in the former, there is the more refined capacity for comprehension. By undue profundity we perplex and enfeeble thought; and it is possible to make even Venus herself vanish from the firmament by a scrutiny too sustained, too concentrated, or too direct.

“The Murders in the Rue Morgue”/ Edgar Allen Poe

the Moment of seeing, or of not seeing

Pastoral/ Forest Gander

Together,

you

standing

before me before

the picture

window, my arms

around you, our

eyes pitched

beyond our

reflections into—

(“into,” I’d

written, as

though there

swung at the end

of a tunnel,

a passage dotted

with endless

points of

arrival, as

though our gaze

started just outside

our faces and

corkscrewed its way

toward the horizon,

processual,

as if looking

took time to happen

and weren’t

instantaneous,

offered whole in

one gesture

before we

ask, before our

will, as if the far

Sonoma mountains

weren’t equally ready

to be beheld as

the dead

fly on the sill)—

the distance, a

broad hill of

bright mustard flowers

the morning light

coaxes open.

I really like this poem and Gander’s reading of it. I was struck by his explanation of the poem, especially the idea that we see all instantly, that seeing, as a process, happens without effort, is immediate, and whole/complete. Occasionally seeing is not like this for many people–they experience visual errors, their brains receive conflicting data from their photoreceptor cells and generates confusing, ambiguous images. More frequently, seeing is like this for me. It is work, and sometimes I can almost feel my brain trying to make sense of an image or a landscape. I witness them changing shape until they settle into what my brain decides they are. But, unlike Gander suggests in his recorded explanation of the poem, I can’t just “look once and find the near and far equally accessible” and the world doesn’t just present itself to me.

I like how Naomi Cohn describes it in her essay, In Light of a White Cane.

What I remember of better eyesight is how the world assembled all at once, an effortless gestalt—the light, the distance, the dappled detail of shade, exact crinkles of a facial expression through a car windshield, the lift of a single finger from a steering wheel, sunlight bouncing off a waxed hood.

Naomi Cohn

For the sighted, seeing is both instantaneous and absolute. To see is to take something in at a glance and possess it whole, comprehending all its complexities. Sight provides instantaneous access to reality. The eye is the window on the world. It’s a perfect little camera, with a lens that automtically focuses the image on a light-sensitive film. Aim, focus, presto —

The sighted can be so touchingly naive about vision. They apparently believe that the brain stays out of it. Or at best, they extend the camera metaphor and envision a tiny self seated inside the skull, passively watching images as they are projected on a movie screen, then pushing the buttons and pulling the levers that will make the body respond appropriately by speaking, running, reaching, or closing the eyes.

Sight Unseen/ Georgina Kleege (96-97)

So if you take anything at all away from this talk tonight, please try to remember: Vision is information processing; it is not image transmission. Your visual system does not just transmit an image of the world up to your brain, because there’s nobody up there to look at an image. There’s nothing up there except nerve cells and all they do is either fire or not fire. So seeing is whether some neurons are firing and some neurons are not and what information those cells are extracting by the firing patterns from the pattern of light that lands on your retina.

vision and art/ Margaret Livingstone

from We grow accustomed ot the Dark/ Emily Dickinson

The Moment – We uncertain step

For newness of the night –

Then – fit our Vision to the Dark

And meet the Road – erect –

from my log entry/ march 19, 2021

The idea of a moment is great–a moment of panic and uncertainty before we’re able to see. As my central vision declines, I have a lot more of these moments: when I enter an unfamiliar building (or sometimes even a familiar one) and not much makes sense. I can’t read the signs or tell where to go. Or when I’m looking at an object but I can’t tell what it is–is it a dead squirrel or a clump of leaves or furry mittens? Most of the time, my brain eventually adjusts and I can see what I’m trying to look at and continue on with more certainty. I’m trying to work on not fearing that uncertain step, letting the moment just be a moment that I will move past, knowing that I will adjust or figure it out (or ask someone for help). And it’s working. I am getting better.

Jenny Xie and Vision/Eyes

Expenditures/ Jenny Xie

Soft, that tear of water. Which signals dreaming’s low

boiling point. I draw down my eyelids, turn my head.

Here, the camera fuzzes. What remains out of focus

is the foreground, the waking forms.

Patterns arise in the sediment: when the eyes adjust,

they’re met with the stutter of faces seasoned.

In Anhui, my birth province:

my unconscious picks up the interference

of my relatives’ dream language, of images that abide

in them. I am closest to their blood

when my memories dream

of theirs, and vice versa, ad libitum.

The relatives here can’t afford self-pity.

If they’ve jotted down lines of verse, I’ve never seen them.

We carry some of the same nerves in the body,

but not the sense of how to exhaust history in ourselves.

Through time’s heavy membrane, mutual recognition presents complications.

Offerings of money, still the shared tongue.

It’s the hands and arms they want me to live inside,

but I take as my home the head.

And how can I be trustworthy with this mouth,

with its tin roof of American English?

To aunts and cousins who speak at me with speed, I lend an ear.

I can’t figure out the source, just the base sentiment.

I distance them at Wuhu train station, where their faces stay.

Days later, I found words dampening against the page.

source: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/777367

Read on Poets & Writers by author.

NY Times article on Jenny Xie’s new collection

Around age 7, Xie became nearsighted. Eyesight has been a source of anxiety in the family, she said; many members have impaired vision and one of Xie’s grandmothers became blind after an ocular hemorrhage.

My parents always sort of instilled in me a fear that my vision was imperiled,” she said, “reading in low light, watching TV, these sources of pleasure were always bound up in the fear that I could lose my eyesight.”

Her fascination with physical vision extends to the interpretation of what is seen: She thinks about how a sight is “constructed and enabled and reinforced” by its context.

There are consequences to how we see, what we see, and also what we allow to remain unseen,” she said.

NY Times article

Visual Orders/ Jenny Xie

[1]

Harvest the eyes from the ocular cavities.

Complete in themselves:

a pair of globes with their own meridians.

[2]

What atrophies without the tending of a gaze? The visible object is constituted by sight. But where to spend one’s sight, a soft currency? To be profligate in taking in the outer world is to shortchange the interior one.

Though this assumes a clean separation, a zero-sum game.

[3]

To draw ink-lines across the lids

To dip into small pots of pigment

To brush two dozen times

To flush with water and tame with oil

To restrain and to spill in appropriate measure

To drink from the soft and silvery pane

To extract the root of the solitary so as to appear

[4]

Describe how the interior looks.

Cloak the eyes.

Close them, and seeing continues.

[5]

The seductions of seeing ensure there is that which remains unseen. Evading visibility is its own fortune. If to behold is to possess, to be looked upon is to be fixed in another’s sight, static and immutable.

[6]

She leans toward the mirror for self-study.

The body canted.

What gets left out?

Uneasy depths.

The fine, lithe needles of the mind.

Endless conversation with no listener.

[7]

Self-consciousness anticipates an excess of seeing. Its incessancy.

Lacan writes, “I see only from one point, but in my existence I am looked at from all sides.”

[8]

Gazed upon

I lose union with the larger surround

Broken from the trance of camouflage

[9]

The acquisitive, insatiable I.

A disembodied eye cannot be confined

to the skin and to what it holds captive.

Inversely, to be unseen against one’s will is to be powerless.

To be denied a reflection and to be locked out of a self.

[10]

What persists down the generations?

The shape of the eyeball, translated by genes.

Mine are long like my mother’s and her mother’s—who was all but blind.

[11]

Ancient optic theory dictates that the eye sends out rays, which touches the object of sight. When the visual ray returns to the eye, the image is impressed on the mind. To see, then, was tactile.

That we are touchable makes us seen.

[12]

Sight is bounded by the eyes,

making seeing a steady loss.

The presence of the unseen has more presence

than that which is exhausted by vision.

We inhabit this incoherence.

[13]

Look at how I perform for you

Look at how you perform for me

An eye for an eye

is how you and I

take on forms in the mind

[14]

Her gaze breaks each time

at the same place.

There is no reversing—

didn’t she know?

She has to go at it from the side.

She has to keep circling.

Naomi Cohn and Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Bird

The eye listens. The song of the red-winged blackbird translated to a sonogram, a shape on a page, a whistle heard in the head that has shape and volume. It triggers a mental image of yellow feet clutching a cattail, of a red quarter circle, so red against glossy black.

An ear sees. As the decay progressed, I began to learn bird song. I invested in “birding by ear” CDs, the little platters spinning endlessly in my cheap boom box. At my most tuned up, I probably knew 150 songs.

I would have kept the old way of looking at a blackbird if I could–it takes a good sized hole in your life to fill all those hours listening to bird tapes.

But there is this to looking at a bird through its song: Your eye, even a good eye, only looks at one thing at a time, only focusses on one bird at a time, but the ear listens in all directions. Paddling across a Canadian lake, red and white pines tall around the shore, the bird song comes from every direction, every compass point, every point on the whole half dome of the world above the water and shore.

Yes. I love this idea of sound coming from every direction, while sight can only come from one. As I was standing at the edge of the sink hole, I was listening in all directions. Sight encourages singularity: single ideas, single perspectives, either this or that but not both at the same time. Hearing encourages plurality: both/and, this and that, multiple perspectives at once.

To see a bird demands both perception and attention. For years I supplied the relatively subtle gaps of perception with attention. Over time, this was not enough. Motion was less my friend. I needed time to make things out, to dart my eye back and forth and up and down to try to get a glimpse of something, to see around the edges of my blind spots, sending a set of broken, incomplete messages to my visual cortex, which on a good day, would assemble a convincing hypothesis of what I was perceiving.

This is all any of us ever do.

Yes! I think this line “This is all any of us ever do” is important. You can read it as metaphor, with blind spots representing those limitations in everyone’s understandings and perspectives. But you can also read it as literal. The more I read about how we see, the more I learn how complicated it is for everyone–good vision or bad—to make sense of images. The brain guesses a lot. Of course, those guesses are better when the brain is given more data, but even then, the brain guesses.

Street lamps and eyes/vision, a few sources

People/ D. H. Lawrence

The great gold apples of night

Hang from the street’s long bough

Dripping their light

On the faces that drift below,

On the faces that drift and blow

Down the night-time, out of sight

In the wind’s sad sough.

The ripeness of these apples of night

Distilling over me

Makes sickening the white

Ghost-flux of faces that hie

Them endlessly, endlessly by

Without meaning or reason why

They ever should be.

The artificial eyes of the street lights, casting their bright gazeless(?) light upon the faces of people walking by.

from Eye Contact/ Craig Morgan Teicher

But is there anything we value so highly

as streetlights, which, unlike bees,

watch over us with their swan-like

necks and open their eyes at the right time

every night? The answer is lonely

from Halos/ Ed Bok Lee

That visual impairment improves hearing,

taste, smell, touch is mostly myth.

With it, however, I can detect

fuzzy spirits exiting buildings;

halos around bikers’ helmets;

each streetlamp another pink-orange dawn.

Ishihara’s Colorblind Plates

note, 11 march 2023: For a few months now, I’ve been working on a series of poems about how I see (and don’t see) color. I want to use the form of a colorblind plate to offer some stories/images/ideas about color. A main goal is to give the reader some insight into how color works for me right now. Eventually I will create a separate space for these poems and all the materials I’ve gathered in connection with them. For now, I’m putting it here.

An inspiration: OR/ Chihyang Hsu

See actual poem here.

OR, 2019

In this piece I quote Homer’s epic poem, The Odyssey, pulling his language to describe the sea. Instead of blue, the poet called the sea “wine-dark”. Conspiracy has it Homer was coler blind and some others say the concept of color blue did not exist in ancient Greek. Using an open-source algorithm to generate the Ishihara plates, a pattern used for a color-blind test, I print the words in dots of color but twist its medical use. BLUE and WINE DARK can be seen by the colorblind while OR can be seen by everyone.

OR/ Chihyang Hsu

A cool idea, and helpful to know that you can get 2 rows of 4 letter words in the plate. At least, that’s what Scott tells me. I can’t see these letters, even when I invert the colors. I am more than colorblind.

A source on Homer and wine-dark

The ancient Greeks and color

Today, no one thinks that there has been a stage in the history of humanity when some colours were ‘not yet’ being perceived. [As they used to think about the ancient Greeks.] But thanks to our modern ‘anthropological gaze’ it is accepted that every culture has its own way of naming and categorising colours. This is not due to varying anatomical structures of the human eye, but to the fact that different ocular areas are stimulated, which triggers different emotional responses, all according to different cultural contexts.

Can we hope to understand how the Greeks saw their world?

Different ocular areas are stimulated, which triggers different emotional responses, all according to different cultural contexts.

There is a specific Greek chromatic culture, just as there is an Egyptian one, an Indian one, a European one, and the like, each of them being reflected in a vocabulary that has its own peculiarity, and not to be measured only by the scientific meter of the Newtonian paradigm.

Can we hope to understand how the Greeks saw their world?

The Greeks were perfectly able to perceive the blue tint, but were not particularly interested in describing the blue tone of sky or sea – at least not in the same way as we are, with our modern sensibility.

More to study: How to make sense of ancient Greek colours

Gray in James Schuyler’s Hymn to Life

The rain stops. April shines,

A Little

Gray descends.

An illuminous penetration of unbright light that seeps and coats

The ragged lawn and spells out bare spots and winter fallen branches.

Yardwork.

What a wonderful description of gray light! It shines a little, an unbright light that seeps and coats and exposes (spells out) the worn spots and the ordinary work needed to be done every spring. Lately, when I think of gray, I think of the opposite — not how it makes everything look shabby, worn, tired, but that it softens everything, making it mysterious and more gentle, relaxed.

It seems like Schuyler could be writing against one classic image of luminous gray light or, it made me think of this at least: the silver lining. Wondering about the origins of the phrase, I looked it up. John Milton’s poem, Comus:

That he, the Supreme good t’ whom all all things ill

are but as slavish officers of vengeance,

Would send a glistring Guardian if need were

To keep my life and homour unassail’d.

Was I deceiv’d, or did a sable cloud

Turn forth her silver lining on the night?

I did not err, there does a sable cloud

Turn forth her silver lining on the night,

And casts a gleam over this tufted Grove.

Thinking about my color poems, and my interest in gray, I wonder how I could write about silver? For me, silver is the color that burns and shines when concentrated on the iced-over river, too bright for my eyes. Silver is also the color of the path when ice is present — it’s a warning sign, a whisper, Watch Out! Slippery.

Eye Contact

Not all of the time, but most of the time (or is it all of the time?), I cannot see the details of people’s faces, especially their eyes. Their head is a gray, fuzzy blob with no discernible eyes, or their eyes are flat, empty orbs. I cannot tell when or if people are looking at me, which often makes me feel less human. This feeling of being less-than-human isn’t helped by the unquestioned “truth” that our eyes are how we access and connect with each other’s Is. I’m collecting examples of this idea — the power of eye contact and the look — to demonstrate that it exists and to interrogate and play with it.

the last stanza from How to Love/ January Gil O’Neil

As they amble away, you wonder if they want

to be startled back into this world. Maybe you do, too,

waiting for all this to give way to love itself,

to look into the eyes of another and feel something—

the pleasure of a new lover in the unbroken night,

your wings folded around him, on the other side

of this ragged January, as if a long sleep has ended.

[Like a white stone]/ Anna Akhmatova – 1889-1966

Translated from the Russian by Babette Deutsch and Avrahm Yarmolinsky

Like a white stone deep in a draw-well lying,

As hard and clear, a memory lies in me.

I cannot strive nor have I heart for striving:

It is such pain and yet such ecstasy.

It seems to me that someone looking closely

Into my eyes would see it, patent, pale.

And, seeing, would grow sadder and more thoughtful

Than one who listens to a bitter tale.

The ancient gods changed men to things, but left them

A consciousness that smoldered endlessly,

That splendid sorrows might endure forever.

And you are changed into a memory.

The Philosopher Did Not Say/ Jennifer Franklin

What secret had Nietzsche discovered

when he walked the Turin streets

before he flung his arms around

a horse being beaten and collapsed

into a decade-long coma? Clinging

to the cowering brown beast, he said

Mother, I am stupid. Wild hair and a three-

piece tweed suit constrained the body

that held the mind that knew too much.

Why am I mining dead men for answers

when they were all as mad as I am?

The horse, his eyes hollow as those

of the Burmese elephant that Orwell shot

decades later, had the look of every

betrayed creature. Perhaps Nietzsche

saw the shock in the animal’s eyes—

how every human contains the capacity

to inflict cruelty. The look that turns

to recognition, to resignation, to an eye

reflecting a field full of fallen horses.

from Rebecca Makkai’s novel, I Have Some Questions

I’d been waiting four years to see Omar, to look him in the eyes. I didn’t want or expect anything from him; I just wanted to see his face.

even if I couldn’t quite tell the color of his cheeks, I could see it in his eyes

I stood beside her, sweating, hands on hips, made eye contact with

her in the mirror.

meaningful eye contact across the dining hall, the kind that said We’d both do best to keep our mouths shut?

The few things I know: She was facing him when he slammed her head back, more than once; they were eye to eye.

When We Look Up/ Denise Levertov – 1923-1997

He had not looked,

pitiful man whom none

pity, whom all

must pity if they look

into their own face (given

only by glass, steel, water

barely known) all

who look up

to see-how many

faces? How many

seen in a lifetime? (Not those that flash by, but those

into which the gaze wanders

and is lost

and returns to tell

Here is a mystery,

a person, an

other, an I?

Elisa Gabbert and the loss of connection during the pandemic

My discussion of her article, A Complicated Energy, in a log entry dated August 26, 2021.

Gabbert laments not being able to see more faces. She misses seeing faces, and she misses seeing faces see her. She is so bothered by this lack of face time that she experiences anxiety, insomnia, and symptoms similar to withdrawal from an anti-depressant. I was struck by discussion here for 2 reasons. First, it gave me more words (and someone else’s words, not just mine) for understanding what I’ve been feeling since 2016 when I stopped being able to see people’s faces clearly. The feelings of loneliness and disconnection, the need to see someone and to see them seeing me. Often I’ve convinced myself that I’m being overly dramatic, that it’s not that big of deal that I can’t see people’s faces, their features, their pupils when they’re talking to me or smiling at me or gesturing to me. But it is. In this essay, Gabbert argues that seeing and being seen are profoundly important–to be seen by others is to become real (and recognized as worthy/worthwhile).

This claim leads me to the second reason I was struck by Gabbert’s words: Why is connection, love, realness so often only (or primarily) understand as an act of sight? This question is not purely academic to me–I post it out of frustration about how the primacy of vision is taken-for-granted–in our everyday thinking and in essays lamenting the loss of connection during the pandemic. With my increasingly limited, unfocused vision, these expressions of recognition and connection are lost on me. Gabbert continues her essay with a discussion of the importance of touch–with a fascinating story about professional cuddlers–so she does offer alternatives to sight for connection. And she offers a broader discussion on the damaging effects of loneliness on our bodies and our mental health. Yet, it still feels like sight and seeing faces are the most important ways of connecting with others. I’d like to find more words about loss of connection that don’t center on faces or seeing. Maybe I’ll have to write them?

Don’t Look Away

added: 2 April 2024 — Again and again, the idea of not looking away from something as a moral imperative or a moral practice arises in poems and ideas I encounter:

This is makes me think of Krista Tippet’s interview with the poet Marie Howe. Howe has some thoughts about the is, which she calls the this, and how we struggle to “stand each is up against emptiness”:

“It hurts to be present, though, you know. I ask my students every week to write 10 observations of the actual world. It’s very hard for them. Just tell me what you saw this morning like in two lines. You know I saw a water glass on a brown tablecloth. Uh, and the light came through it in three places. No metaphor. And to resist metaphor is very difficult because you have to actually endure the thing itself, which hurts us for some reason….We want to — we want to say it was like this. It was like that. We want to look away, and to be, to be with a glass of water or to be with anything. And then they say well there’s nothing important enough. And then it’s whole thing is that point.”

31 may 2017

This might be the most difficult task for us in postmodern life: not to look away from what is actually happening. To put down the iPod and the e-mail and the phone. To look long enough so that we can look through it—like a window.

Not to Look Away/ Marie Howe, discussed on 17 july 2020

An occasional poem by Danni Quintos:

Once I wrote a poem on a bridge

because you told me to find my ghosts.

I remembered you once said, Our job as poets

is to not look away. I looked & wrote

the scariest thing I could think & after

you read it, you gave me a book

(to borrow) which I hugged so hard

that the million synonyms inside

could hear my heart beating.This looking, described above by Finney and Quintos, this black-eyed opening—this not looking away—is a poetics, yes, but as any poetics is, it is also an ethics. What we look at, what we see, and how, and if we say what we see, is an ethics. Tender black looking with the light coming through is an ethics. Kin to testimony. Kin to witness, I think I’m saying. I will not not see you, Finney’s work repeatedly insists. I will look and say what I see. This witness is my occasion. With my pencil behind my ear.

Be Camera, Black-Eyed Aperture / Ross Gay

Unable to see faces, often staring into a void or a smudge or a darkness, it is hard to see, difficult to not look away. How do I reimagine this ethical beholding in ways that I can practice? What might not looking away mean without the looking? Not turning away?

This is a problem of language, and more than a problem of language, I think.

Behold is to eyes as ___ is to ears?

An ear-witness?

Does not turning away work here? What about facing or keeping open?

How I see

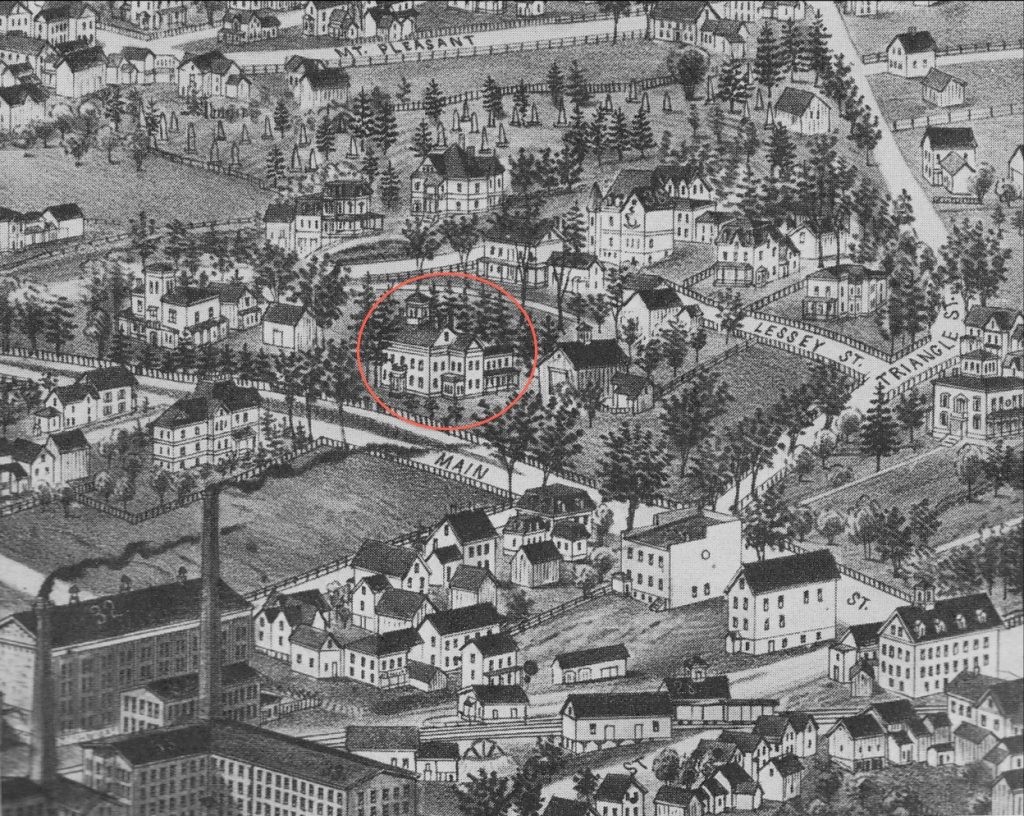

I started reading it, and encountered a map of Amherst with a note: The Dickinson house is circled in red.

Can you easily see the red circle? I can’t. The only way I am able to see it is if I put my face up right against the screen and look at it through the side of my eye. Only then do I see a trace of red — the idea of red. Once I see (or feel?) the red, I can see a faint circle and I can tell that it’s red, but it’s not RED! but red?

The other day, Scott, FWA, and I were discussing the scenes in Better Call Saul that are set in the present day and are in black and white. Scott and FWA both agreed that those were harder to watch — they had to pay more careful attention — because they lacked color, which is harder because visual stories often rely heavily on color to communicate ideas/details. I said I didn’t realize that they were in black and white; they didn’t look any different to me than the other scenes, which are in vivid color (at least that’s what they tell me). I realized something: it’s not that I don’t see color, it just doesn’t communicate anything to me, or if it communicates it’s so quiet that I don’t notice what it’s saying.

Back to the image with the red circle. The main point of the image is to enable you to quickly and easily see where the Dickinson home is located in the town. If I hadn’t read the text below it, I never would have known there was a circle, and the main point of the image would be lost on me. This happens a lot. Things that are obvious to most people, aren’t to me. More than that, they don’t exist. Of course it’s very frustrating and difficult, but it’s also fascinating to recognize this, and helpful to understand it.