unmappable, unlocatable, uncertain, confused, not knowing, unknowing, illegible

- Bewilderment/ Fannie Howe

- Bewilderment is at the core of every great poem

- The Poetics of Bewilderment

- Less Than Certain

Dear Wilderness

Alone in the forest, stranded at sea, wandering in the desert—the kinds of stories that move me are the ones where we continue to find ourselves shrouded in the unknowingness of being. Every day begins and ends like this: the galaxies are ever moving away from you. Inside the planetarium, I leaned into the swathy darkness, and somewhere scientists sensed an unknown, invisible web holding the universe together, to which they gave the name “dark matter” and “dark energy.” Projected on the ceiling, it looks like a vast and intricate skein parachuting our bodies. In my favorite essay by Fanny Howe, she starts, “Bewilderment as a poetics and an ethics,” and from the body of text that follows, a vocabulary emerges like a collection of nodes: mystery, hidden, unlocatable, complexities, perplexities, errancy, fluidity, spiraling

Bewilderment, Unknowing, and my Vision

knowing and not knowing, embracing the uncertainty of never really knowing and accepting that knowing exactly what my vision problem is won’t make a difference in my treatment (there is none) or the speed at which my central vision deteriorates. And, in fact, knowing is not possible. This not knowing is not ignorance–more like never knowing enough, having perpetually incomplete knowledge, the impossibility of KNOWING.

bewilder or be wilder?

the wilderness within us is the space/place/opportunity for joy, mystery, astonishment, wonder, delight

wilderness defined by McKay, Vis a Vis:

capacity of all things to elude the mind’s appropriations

Ross Gay’s The Book of Delight

The body, the life, might carry a wilderness, an unexplored territory, and that yours and mine might somewhere, somehow meet. Might even join.

And what if the wilderness–perhaps the densest wild in there–thickets, swamps, bogs, uncrossable ravines and rivers–is our sorrow?

getting lost

This is one of many poems I wrote in a short period of time early last year, when I stepped away from writing The Crying Book-—my first work of nonfiction—to return to my home form. I was seeking all sorts of wisdom from Merriam-Webster, trying to understand what layers there are to the words I think and speak, finding shiny edges I hadn’t known before: new to me, but long-known to the words themselves. Then, as one does, I followed the words into a figurative space, where they invited me to get lost. I’m never able to get quite as lost as I want to, but with each poem I get a little closer (Heather Christie discussing her poem, “What Big Eyes You Have”).

SOJOURNS IN THE PARALLEL WORLD/Denise Levertov

We live our lives of human passions,

cruelties, dreams, concepts,

crimes and the exercise of virtue

in and beside a world devoid

of our preoccupations, free

from apprehension—though affected,

certainly, by our actions. A world

parallel to our own though overlapping.

We call it “Nature”; only reluctantly

admitting ourselves to be “Nature” too.

Whenever we lose track of our own obsessions,

our self-concerns, because we drift for a minute,

an hour even, of pure (almost pure)

response to that insouciant life:

cloud, bird, fox, the flow of light, the dancing

pilgrimage of water, vast stillness

of spellbound ephemerae on a lit windowpane,

animal voices, mineral hum, wind

conversing with rain, ocean with rock, stuttering

of fire to coal—then something tethered

in us, hobbled like a donkey on its patch

of gnawed grass and thistles, breaks free.

No one discovers

just where we’ve been, when we’re caught up again

into our own sphere (where we must

return, indeed, to evolve our destinies)

—but we have changed, a little.

I love the idea of nature not caring about our preoccupations and of living in and beside it and of a moment or an hour in which we can drift and lose track of ourselves as we respond to nature–which is, by the way, what running enables me to do by the gorge for at least a few seconds every time I run. I also love how she describes nature in such simple forms: cloud, bird, fox. With my vision and how it makes objects fuzzy, sometimes all I can recognize is the basic form: person, tree, boulder, river, bird

This valuing of losing track of ourselves is central to my own goals and has me thinking that it is just as or more important than the constant refrain to find ourselves.

What would it look like to center/prioritize losing instead of finding ourselves?

Lost/ David Wagoner

Stand still. The trees ahead and bushes beside you

Are not lost. Wherever you are is called Here,

And you must treat it as a powerful stranger,

Must ask permission to know it and be known.

The forest breathes. Listen. It answers,

I have made this place around you.

If you leave it, you may come back again, saying Here.

No two trees are the same to Raven.

No two branches are the same to Wren.

If what a tree or a bush does is lost on you,

You are surely lost. Stand still. The forest knows

Where you are. You must let it find you.

learning/knowing/Knowing

Epistemology/ Catherine Barnett

Mostly I’d like to feel a little less, know a little more.

Knots are on the top of my list of what I want to know.

Who was it who taught me to burn the end of the cord

to keep it from fraying?

Not the man who called my life a debacle,

a word whose sound I love.

In a debacle things are unleashed.

Roots of words are like knots I think when I read the dictionary.

I read other books, sure. Recently I learned how trees communicate,

the way they send sugar through their roots to the trees that are ailing.

They don’t use words, but they can be said to love.

They might lean in one direction to leave a little extra light for another tree.

And I admire the way they grow right through fences, nothing

stops them, it’s called inosculation: to unite by openings, to connect

or join so as to become or make continuous, from osculare,

to provide with a mouth, from osculum, little mouth.

Sometimes when I’m alone I go outside with my big little mouth

and speak to the trees as if I were a birch among birches.

I’m not sure what I think about the first line: “Mostly I’d like to feel a little less, know a little more.” I’ve been writing a lot about the limits of knowing and the need to feel the force of ideas more. Yet, I like this idea of knowing as becoming familiar with things (knowing knots) and acquiring interesting facts (about preventing fraying, how trees communicate). I’d like to distinguish between knowing as familiarity and knowing as conquering/mastering/fully understanding. I’d also like to put this poem next to another poem I discovered this fall, Learning the Trees, which I posted in my sept 15 log entry. I want to ruminate some more on the difference between learning and knowing and Knowing.

Some problems with naming and knowing

“The birds know who they are. They don’t need you to tell them…“

[Orinthologist Drew Lanham responding to Krista Tippet’s confession that she doesn’t know the names of birds and is ashamed of not knowing]

Well, it’s not a problem. There’s no shame in not knowing the name of a bird. If it’s a redbird to you, it’s a redbird to you. At some point, as a scientist, it’s important for me to be able to identify birds by accepted common names and Latin names and those things. But then I revert frequently to what my grandmother taught me, because, I say, the birds know who they are. They don’t need you to tell them that.

But over time, when we relax into a thing and maybe just being with a bird, then your brain kind of relaxes, it loosens, and things soak in. And I think that’s the key with a lot of learning. But not getting the name right immediately does not in any way diminish their ability to appreciate “the pretty,” as Aldo Leopold talks about. And so seeing that bird and saying, “Oh my God, what is that? Look at it,” and you’re looking at it, and you can see all of these hues, and you can watch its behavior, and you may hear it sing — well, in that moment, it’s a beautiful thing, no matter what its name is.

Sometimes, what I try to get people to do is to disconnect for a moment from that absolute need to list and name, and just see the bird. Just see that bird. And you begin to absorb it, in a way, in a part of your brain that I don’t know the name of, but I think it’s a part of your brain that’s also got some heart in it. And then, guess what? The name, when you do learn it, it sticks in a different way.

take a moment to not know and just see the bird, be with the bird

This reminds me of Mary Oliver’s poem “The Real Prayers Are Not the Words, But the Attention that Comes First“

Learning the Trees/ HOWARD NEMEROV

Before you can learn the trees, you have to learn

The language of the trees. That’s done indoors,

Out of a book, which now you think of it

Is one of the transformations of a tree.

The words themselves are a delight to learn,

You might be in a foreign land of terms

Like samara, capsule, drupe, legume and pome,

Where bark is papery, plated, warty or smooth.

But best of all are the words that shape the leaves—

Orbicular, cordate, cleft and reniform—

And their venation—palmate and parallel—

And tips—acute, truncate, auriculate.

Sufficiently provided, you may now

Go forth to the forests and the shady streets

To see how the chaos of experience

Answers to catalogue and category.

Confusedly. The leaves of a single tree

May differ among themselves more than they do

From other species, so you have to find,

All blandly says the book, “an average leaf.”

Example, the catalpa in the book

Sprays out its leaves in whorls of three

Around the stem; the one in front of you

But rarely does, or somewhat, or almost;

Maybe it’s not catalpa? Dreadful doubt.

It may be weeks before you see an elm

Fanlike in form, a spruce that pyramids,

A sweetgum spiring up in steeple shape.

Still, pedetemtim as Lucretius says,

Little by little, you do start to learn;

And learn as well, maybe, what language does

And how it does it, cutting across the world

Not always at the joints, competing with

Experience while cooperating with

Experience, and keeping an obstinate

Intransigence, uncanny, of its own.

Think finally about the secret will

Pretending obedience to Nature, but

Invidiously distinguishing everywhere,

Dividing up the world to conquer it,

And think also how funny knowledge is:

You may succeed in learning many trees

And calling off their names as you go by,

But their comprehensive silence stays the same.

who gets to name and what power, what violence is involved in that naming?

…thinking about who gets to tell the story and the names — and so I’m intensely interested in language and what different people call things, and these names and what names mean. So that Indigenous and First Nations people, who have all of these languages, and who a raven is to one nation versus who the raven is to another nation or people within that nation. So all of that is important, I think, for us to pay attention to, and all of those are different ornithologies.

In Western science, we boil down to Latin binomial and to genotype and phenotype; and all of that is critical, and it’s important in what we do as scientists. But I think, again, broadening the scope of vision so that we see the big picture — we need to understand who birds are to others, what land is to others; that if my ancestors were forced into nature and hung from trees, I might not have the same interest in going out into the forest and naming the trees.

On Being episode with Drew Lanham

See this thread about strange/ridiculous/problematic bird names.

unknowingness

What moral resources might we draw upon to help us resist the urge to shore up our unknowingness and assert our “truths” in violent ways and what type of character must we cultivate in order to embrace “unknowingness at the core of what we know, and what we need…” (Undoing Gender, 227)?

discomfort

The aim of discomfort is for each person, myself included, to explore beliefs and values; to examine when visual “habits” and emotional selectivity have become rigid and immune to flexibility; and to identify when and how our habits harm ourselves and others (Megan Boler, 185-186).

The first sign of the success of a pedagogy of discomfort is, quite simply, the ability to recognize what it is that one doesn’t want to know, and how one has developed emotional investments to protect oneself from that knowing. This process may require facing the “tragic loss” inherent to educational inquiry; facing demons and a precarious sense of self. But in so doing one gains a new sense of interconnection with others. Ideally, a pedagogy of discomfort represents an engaged and mutual exchange, a historicized exploration of emotional investments. Through education we invite one another to risk “living at the edge of our skin,” where we find the greatest hope of revisioning ourselves (200).

a dreamlike state

Less than Certain: How to Teach Bewildering Poems

We are taught/ disciplined to be certain: “When encountering Chen’s sui generis mango, my student’s first instinct—perhaps instilled in high school, perhaps innate to the practice of close reading—was to determine for certain what it was doing in the poem. If you’re taught that every instance of an apple is an allusion to Genesis 3:5–22, then what exactly must a mango signify?”

teach students how not to understand a poem and to embrace that not everything in a poem can ever be understood, even by its author

a prayer: make me less certain

When you’re asking what the role of a poet is in a society, in a culture, in a country, in a community, it is to respond in the way that only poetry can….

Jane Hirshfield Interview

Poetry summoning is to transcend easy language, platitudinous language, slogans that make people stupid and that separate them from one another. And so part of the role of poetry and poets is, I think, to force ourselves past the common ways of looking at things by being more responsive and finding the uncommon, original, sidelong, nuanced, subtle, and not strive for the certainty which seems such a bane of our current discourse.

epistemology of doubt: “The difference between myself and a student is that I am better at not knowing what I am doing.”

In her introduction to Madness, Rack, and Honey, Ruefle suggests that poetry maintains its mystery by always being a few steps beyond us. She likens attempting to describe poetry to following a shy thrush into the woods as it recedes ever further, saying: “Fret not after knowledge, I have none.” Ruefle proposes that a reader might “preserve a bit of space where his lack of knowledge can survive.”

Human Lessons: On Mary Ruefle’s My Private Property

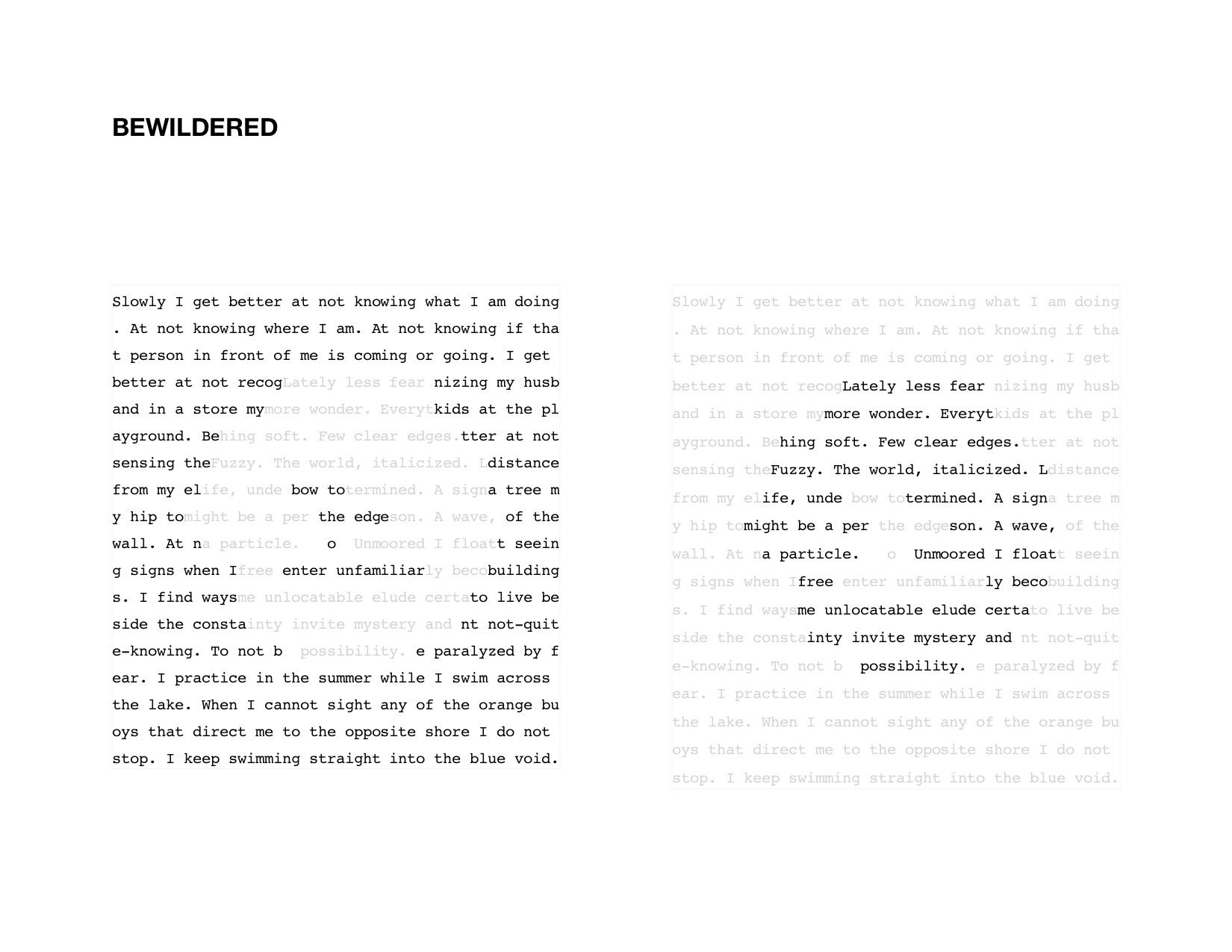

Bewildered/ Sara Lynne Puotinen

surprise as a bridge between bewilderment and wonder?

See this thread about surprise in poetry

What is the wild in poetry?

From S1E4 of The Slave is Gone, Power, Poetry & Sex in Apple TV’s Dickinson

Brione Janae (Breezy): At its best, maybe some of the energy that drives the poem. You think of the wildness of the poet, that energy, especially when I’m really on and I’m like, I want to write. I need to write. It’s like a wild type of energy.

Jericho Brown: When you say the wild, I think of the phrase, going out into the wild and how that’s about getting yourself ready and prepared for going out to have an experience where you hope something happens that you didn’t know was going to happen because it’s the wild. You want to see something you otherwise would not see, hear something you otherwise would not hear, or feel a way you would otherwise not feel. And you’re willing to sweat for it. If you go out into the wild you’re gonna sweat, you’re gonna get bit by mosquitos, you’re going to be tired of walking, sleeping on the ground. None of that is a good time. So there’s a way that it’s the feeling you have when you’re in a poem and you’re writing and you have no idea what you’re saying, but you need to get a poem where you do what you’re saying.

Ada: The wild is that part of me that feels the most free and the most unexpected. No one is requiring anything of that freedom, of that person, of that thing underneath the thing, the animal underneath the animal, the voice underneath the voice. And I feel like it’s that kind of freedom that can be a little dangerous and a little scary. You don’t know what’s going to happen with that wild. I think that’s my favorite part of poetry that I am not in control of this because of when I think of wild, I think of untamed. Once we edit there’s a certain amount of taming that happens, but when it actually happens and we’re making, it’s a free thing.

What is wilderness?

Thoreau’s argument about going for a walk was an argument for wildness, which for him was also rumination, the freedom to think, to loose his spirit into the world and be open to possibility. To live in the present. But what’s left of the wilderness? When plastic particles have been found at 30,000 feet, atop the most remote mountains, when our acidifying oceans choked with oil and chemical sunscreens cause mass fish die-offs, how can we feel we are creatures frolicking in some pristine wild? Our human impact can be seen everywhere we look, and if I’m honest with myself, I can’t say I’m not implicated in this harm.

—

Perhaps the wilderness is lost; we’ve reached the western edge and developed every inch. The forests are all on fire. Still, when I run, I enter my animal body, I bask in the air shearing my skin, the crust of salt that forms at my hairline. I smell eucalyptus and redwood mingled with ripe compost in a bin for the waste management truck to pick up.

Why I Run/ Rachel Richardson

To acknowledge mystery is a sign of respect and a form of faith

To acknowledge limits to wht we can know about a thing–to acknowledge mystery–is not, to my mind, an admission of feafeat by mystery but instead a show of respect for it, and to this extent–I mean this as seculalry as possible–it’s a form of faith (1).

My Trade is Mystery/ Carl Phillips